Knights of the Air

The Transition from Cavalry to Air Warfare, the age of the Red Baron and Werner Voss

For thousands of years, the horse had been the decisive factor in combat... from the powerful knightly orders of the European Middle Ages to the highly mobile Scythians, who so easily outmaneuvered massive invading armies due to their unmatched advantage in mobility and reconnaissance—all the way back to the peoples descended from the Yamnaya and Sintashta, and the devastatingly effective war chariots of ancient Arya nobility.. the horse had long represented a core element of martial dominance.

Yet, all things change, with time...

World War I marked a significant shift in military tactics, as trench warfare and the increased firepower of modern armies rendered traditional cavalry charges obsolete— sidelining a force often led by aristocratic and noble officers who could no longer fulfill their roles in recon and rapid assault. The skies became the new frontier, offering similar prestige and adventure reminiscent of the chivalric ideals of their cavalry heritage.

This shift—from piloting powerful beasts on the battlefield to commanding powerful marvels of engineering in the air—has always fascinated and intrigued me. Just as knights of old were revered for their bravery and skill in combat, the intrepid pilots of the First World War emerged as the new heroes, their high-stakes aerial duels captivating a world in flux. In this transformed era, the skies over Europe became the jousting fields where honor and valor were tested, with airmen celebrated like knights for their individual prowess and courage, their dogfights a contemporary joust where skill and bravery crowned the victor.

From the early pioneer aces and teachers like Boelcke and Immelmann, to the legends of Richthofen and Voss, this was a brave new age of aerial cavalry and chivalry.. and an arena in which merit and ability were everything—in which anyone might make his way exclusively via his own talents and skills, with men matching wits and abilities directly against their fellow man in the most forthright and direct manner, in deadly duels in which often only one would be flying home afterward.. and where the best among these might become legends.

"The great thing in air fighting is that the decisive factor does not lie in trick flying but solely in the personal ability and energy of the aviator."

~ Manfred von Richthofen

In an era of brutal trench warfare, often characterized by muddy, cramped, unpleasant and chaotic conditions, the privilege to soar above it all was a very real one... even if the risks were far greater and the chances of survival were lower, several ace pilots were as thankful for the opportunity as they were to the brave men they soared above—in mutual recognition that each was fulfilling their specific role for the greater good.

In this infancy of flight, in relatively experimental machines they were tasked not just to fly and land successfully—in nearly every sort of environmental or weather conditions, from within complicated types of machines that didn’t even exist a few years prior—but often to evade or shoot down enemy planes as they did so. These were all men of tremendous courage.. and because skill, discipline, and a calm, collected confidence were almost always the deciding factors, those men who became great aces had proven themselves, definitively, to be extremely capable. Their nations were right to honor them, their people right to celebrate them.

Men like the Canadian Billy Bishop, the highest-scoring non-European ace of the war with 72 confirmed victories—an incredible tally for a fearless pilot known to frequently fly alone into enemy territory.

A man who once attacked an entire German airfield solo, shooting down three enemy planes as they attempted to take off, taking heavy anti-aircraft fire but managing to limp back to base in one piece, earning him the Victoria Cross, the highest military honor in the British Empire.

Or the Frenchman René Fonck, the highest-scoring non-German ace of the war with at least 75 victories, who favored a more precise and calculated style.

This methodical style, mastery of aerial gunnery, combined with exceptional eyesight and instincts, made him not simply one of the greatest pilots in aviation history, but led to heroic feats like the downing of six planes in a single day on May 9, 1918, and helped keep him alive to serve his nation after the war. Unjustly attacked in our age for his friendship with ace WW1 German pilots Hermann Göring and Ernst Udet

and his later participation in Vichy France in WW2 (Vichy Foreign Minister Pierre Laval claimed that Fonck had recruited 200 French pilots to fight on the National Socialist side), his attitude simply reflected an almost universal mindset of mutual respect and brotherhood among the best of the best in the sphere:

Among all who’d regularly risked their lives to prove themselves and their courage, honor, and love for nation—and then proceeded to not just survive but to positively thrive under difficult conditions that might break many weaker men—there existed a special camaraderie and kinship.

The respect for excellence often transcended mere politics, or even national borders. It was something in the blood.

There were also several nobles and royalty that took to the skies for their nations—and perhaps, for the adventure of it all.

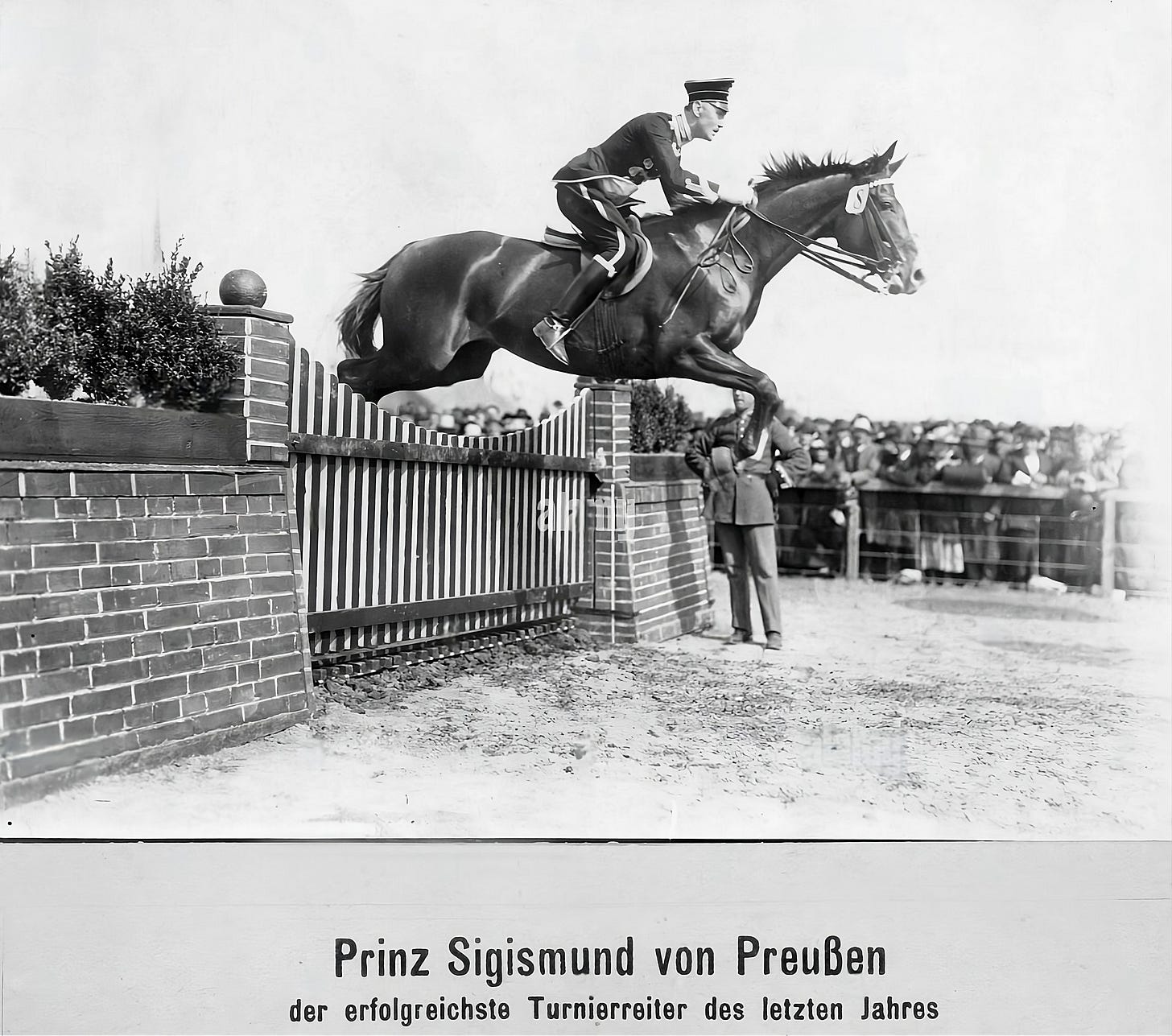

Prince Friedrich Karl of Prussia1 was a German prince and competitive horseman who competed in the 1912 Summer Olympics, winning a bronze medal.

His brother Prince Friedrich Sigismund, another expert horseman (widely considered to be one of the best in Germany).

And yet another member of the German (minor) nobility, widely hailed as the greatest ace of them all, will be our main focus here:

Manfred von Richthofen, ‘The Red Baron’.

With 80 confirmed kills (with the actual figure likely much higher, as formal confirmation often became tricky as the war heated up), famed in part for painting his plane the brightest red—as if to openly challenge his opponents with the opposite of camouflage—Manfred is forever ranked #1 among the air aces of WW1... achieving an exceptional legendary status he’d not live to enjoy, and yet would make his name immortal.

Richthofen’s red steed, a blazing symbol of defiance in the skies, not only crowned him the ultimate ace, but also inspired a new era of aerial warfare where individual valor intertwined with national ambitions... his daring exploits, shared through tales of dogfights and trophies, ignited the imaginations of pilots and engineers alike, fueling a relentless pursuit of supremacy in the air. As the Red Baron’s legend grew, so too did the realization that victory in this new form of joust demanded more than courage—it required machines as bold and brilliant as the men who flew them, setting the stage for an unprecedented race to master the skies.

The Race for Supremacy Begins

Air supremacy was a crucially important factor from WW1 onward, leading to an arms race and a race for piloting skills between all nations. A significant part of the equation was the engineering talent—the discipline, creativity, and artistry that went into creating and improving the planes themselves—and the other element in the equation was the aptitude of the aviators themselves.

Germany, naturally, excelled in both spheres.. and is perhaps the most intriguing choice of focus for this article—as the nation with the largest percentage of leading pilots and top aces in both World Wars, and an impressive and well-documented air combat tradition.

Beginning with men like Oswald Boelcke, widely hailed as ‘The Father of German Fighter Aviation’, and Max Immelmann, the first pilot to achieve ace status, a new age was born... and immediately men sought out that type of excellence and mastery that would come to so define the best of the best in this sphere.

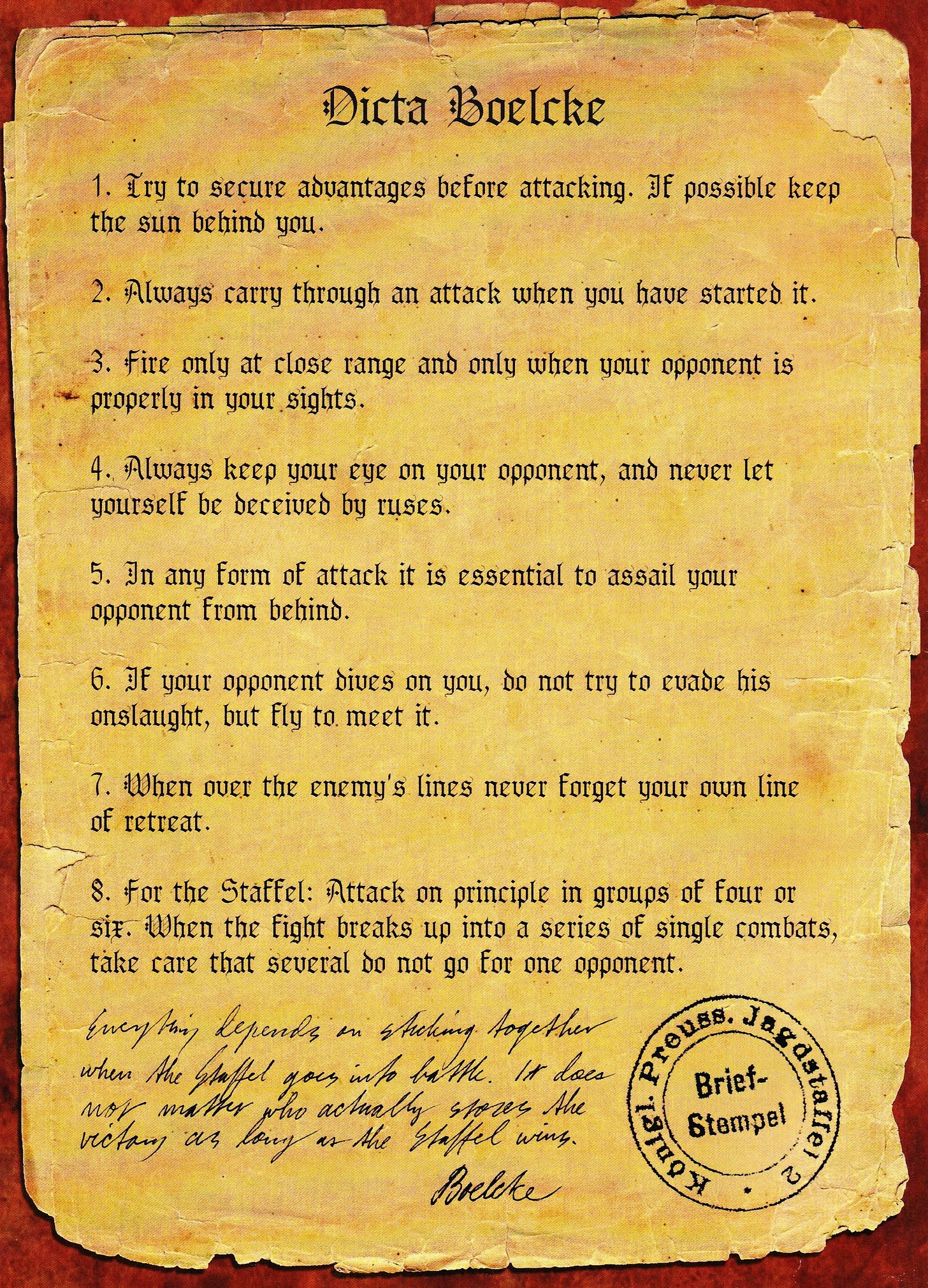

Immelmann and Boelcke were the first to receive the Pour le Mérite2 , in January of 1916. Oswald would go on to be revered for his ‘Dicta Boelcke’, the first manual of fighter tactics distributed service-wide...

as well as his expert guidance and mentorship of promising fliers and his reorganization of the German air force to effectively gain supremacy on the Western Front. Max became famed for exceptional piloting and pioneering new tactical innovations, with the trademark “Immelmann turn”3 being a prime example.

It’s said that during Immelmann’s very first engagement, his gun jammed... yet, he somehow managed to clear it while flying with both hands off the controls, showcasing unique skill and a promising courage and composure under pressure.

"Like a hawk, I dived ... and fired my machine gun. For a moment, I believed I would fly right into him. I had fired about 60 shots when my gun jammed. That was awkward, for to clear the jam I needed both hands—I had to fly completely without hands ... Lieutenant William Reid fought back valiantly, flying with his left hand and firing a pistol with his right. Nonetheless, the 450 bullets fired at him took their effect; Reid suffered four wounds in his left arm, and his airplane's engine quit, causing a crash landing."

- Max Immelmann

This victory marked the beginning of the ‘Fokker Scourge’, a period when German pilots, equipped with the new Fokker Eindecker fighter planes, absolutely dominated the skies, inflicting heavy losses on Allied air forces. Immelmann’s success during this time made him a national hero, and earned him the nickname "Der Adler von Lille" (The Eagle of Lille).

Meanwhile, Boelcke’s unique fighting style—whether purposeful or not, it’s difficult to say—frequently saw his opponents falling to earth in a deadly ball of flame, as opposed to the more tame takedown victories experienced by many... yet, on September 2, 1916, he managed to force down the aircraft of one Robert Wilson, a British captain. In a testament to the magnanimity of the age and its great men, and perhaps helping set the tone for the treatment of ace pilots by one another, Boelcke invited him to tea and later to dine with his squadron, treating him with respect before arranging for his transfer to a prisoner-of-war camp.

Immelmann and Boelcke, these two giants of their arena, gradually became beloved national celebrities.. and an amicable and sporting rivalry continually pushed them to new heights as they began trading the title of highest-scoring ace back and forth.

A Torch is Passed

Despite all Boelcke accomplished—forever changing the art and discipline of air warfare and literally writing the book on the topic—it may be that his greatest claims to fame were in the masterful pupils he so effectively tutored and mentored, laying the ground work for the entire German air force to come.

"On the 17th September, 1915, I shot down my first Englishman. It was near Cambrai. I was flying with Boelcke's squadron. We were seven against seven English two-seaters. I selected one of them and fired. After a short struggle, I hit the engine. The Englishman had to land near our flying ground. Both the pilot and the observer were severely wounded. The observer died immediately; the pilot died on his way to the dressing station. I honored the fallen enemy by placing a stone on his beautiful grave."

~ from the journal of Manfred von Richthofen

The greatest of these, Manfred von Richthofen himself, was to witness his great teacher die in a tragic collision on October 28, 1916, during a dogfight near Douai, France.

The death hit Boelckes apprentice pilots—and the entire nation of Germany—like a blow. Though Oswald was young, his brilliant students were often far younger, and had gradually come to view him as something of a father figure.. one who was simultaneously a great friend, a model soldier, and quite simply an exceptional man.

Manfred would write:

“One could hardly conceive of it ..”

“Boelcke is no longer among us now. It could not have hit us pilots any harder ..”

“I am after all only a combat pilot, but Boelcke, he was a hero”.

Among the tributes, the Royal Flying Corps air-dropped a wreath with the inscription, "To the memory of Captain Boelcke, our brave and chivalrous opponent." Another wreath came from captured British pilots, including Captain Wilson, whom he’d treated to tea, reading, "To the opponent we admired and esteemed so highly."

With Immelmann also having fallen in June of the same year, the baton had now officially been passed to their students.. and time would soon tell just how well they’d done their job.

The Red Baron

Manfred Albrecht Freiherr von Richthofen, born in Breslau, Germany, into Prussian nobility on May 2, 1892, showed early prowess in horse riding and hunting, later serving as a cavalry officer and earning an Iron Cross for bravery before transferring to the air service in 1915.

"I am a Richthofen. The Richthofens have always lived in the country. They owned landed estates. The first General in our family was my grandfather's cousin. He was a cavalry general, and he died as a colonel-in-chief of the 1st Silesian Uhlans..

My mother belongs to the family Von Schickfuss und Neudorf. Their character resembles that of the Richthofen people. There were a few soldiers in that family. All the rest were agrarians. The brother of my great-grandfather Schickfuss fell in 1806. During the Revolution of 1848 one of the finest castles of a Schickfuss was burnt down. The Schickfuss have, as a rule, only become Captains of the Reserve.

In the family Schickfuss and in the family Falckenhausen—my grandmother's maiden name was Falckenhausen—there were two principal hobbies: horse riding and game shooting.”

Excerpt from Manfred’s work, ‘The Red Battle Flyer’ (https://www.gutenberg.org/files/41159/41159-h/41159-h.htm)

He took to it naturally, learned quickly, and had of course been blessed to be shaped and oriented by perhaps the best teacher in the world in Oswald Boelcke, a man who’d immediately recognized something special in Manfred, and tried his best to nurture and cultivate it.

Richthofen’s early writings capture his excitement for flying. "My first flight as an observer was a great experience. I was very excited, but I did not feel any vertigo. I felt quite secure in the aircraft." Marveling at the aerial view, "From above, Cologne and its cathedral looked like toys. I wanted to fly all day." Even his early adventures showed his willingness to take on risk—"We flew over burning Wicznice. The smoke was at 6,000 feet, while we were at 4,500 feet. We nearly crashed, but Holck's skill saved us. We landed in an abandoned Russian artillery position." Once he had a taste for the air, he seemed to want nothing else... he only needed this passion to be honed by masters like Boelcke.

The new star pupil sprung from impressive stock.

Not only would his brother Lothar go on to be a great ace and one of the most roundly competent pilots of his age, but his cousin, Ferdinand von Richthofen, a famed explorer and scholar renowned for his work in geography and geology, is a man so prolific I’ve quoted him myself more than once, in my own historical works.

Often called one of the founders of modern geography, Ferdinand was a giant in his own sphere and, interestingly enough, is apparently the man responsible for coining the term ‘Silk Road’.

Wolfram von Richthofen, a cousin, would later go on to be a respected and accomplished Generalfeldmarschall in World War II, known for tactical air warfare leadership.

Like so many other German pilots, the Richthofens sprung from an equestrian family, with many of the men in their families becoming cavalry officers or athletes in related fields. Like so many of their time, as the utility of cavalry faded, they became pioneers in advancing this new age, this intriguing new discipline.

Under Boelcke’s sage guidance in Jagdstaffel 2 (Jasta 2), Richthofen scored his first aerial victory on September 17, 1916, downing a British aircraft near Cambrai—a milestone that marked the beginning of his ascent as a fighter pilot. In the weeks that followed, he continued to refine his skills, achieving ten confirmed kills by November 1916. His tactical prowess—particularly his method of stalking opponents from above and using the sun to his advantage—quickly earned him a growing reputation as one of Germany’s most promising aces.

As the reputations of ace pilots around the world grew, the public became increasingly enthralled with kill counts, which nations would often publicize for propaganda purposes. Far from a perfect measure4, kill counts provided at least something definitive and quantifiable that the average person could easily understand, offering some indication of how nations were faring against one another, and how individual pilots were performing relative to their peers... and no pilot was faring better than the famed Boelcke pupil, Manfred von Richthofen.

After the death of his teachers and mentors, and after clearly distinguishing himself as a most capable pilot and tactician, he swiftly rose through the ranks to positions of ever greater leadership and influence. This rapid rise and increasing renown set the stage for a defining moment in his career.. and on November 23rd, 1916, he was to face his first major test:

Master vs Master

As Richthofen approached his British foe on a late November evening, he had no way of knowing the caliber of foe he was about to engage. Lanoe Hawker, a Victoria Cross5 bearing British ace with the infamous motto ‘attack everything’, was both powerfully competent and extremely aggressive.. and for the next full 30 minutes—an extraordinarily long time relative to most engagements of the age—the two masters expertly contested with one another in the skies above Bapaume, France.

"My Englishman was a good sportsman, but by and by the thing became a little too hot for him. He had to decide whether he would land on German ground or whether he would fly back to the English lines. Of course, he tried the latter, after endeavoring in vain to escape me by loopings and such tricks. At that time my first bullets were flying around him, for so far neither of us had been able to do any shooting. When he had come down to about 300 feet, he tried to escape by flying in a zigzag course, which makes it difficult for an observer on the ground to shoot. That was my most favorable moment. I followed him at an altitude of from 250 to 150 feet, firing all the time. The Englishman could not help falling. But the jamming of my guns nearly robbed me of my success."

After using an unusual number of rounds on his skilled opponent, Richthofen’s final burst of gunfire struck Hawker in the back of the head, killing him instantly. Hawker’s aircraft crashed 200 yards east of Luisenhof Farm, just south of Bapaume, on the German side of the front lines.. becoming Richthofen’s 11th victory, and earning his respect.

"My eleventh Englishman was a Major Hawker, twenty-six years old and commander of an English squadron. According to prisoners’ accounts, he was the English Boelcke. He gave me the hardest fight I have experienced so far, until I finally succeeded in getting him down."

He’d promptly hang Hawker's gun over his door as a souvenir, and a reminder.

Rising to Command

As of the date in which Manfred took command of Jasta 11 in January 1917, the unit had been struggling... yet it quickly rose to fame under his leadership. Already an ace with 16 victories, he immediately set about introducing new discipline and tactics and freshly reorganized and reinvigorated the unit.

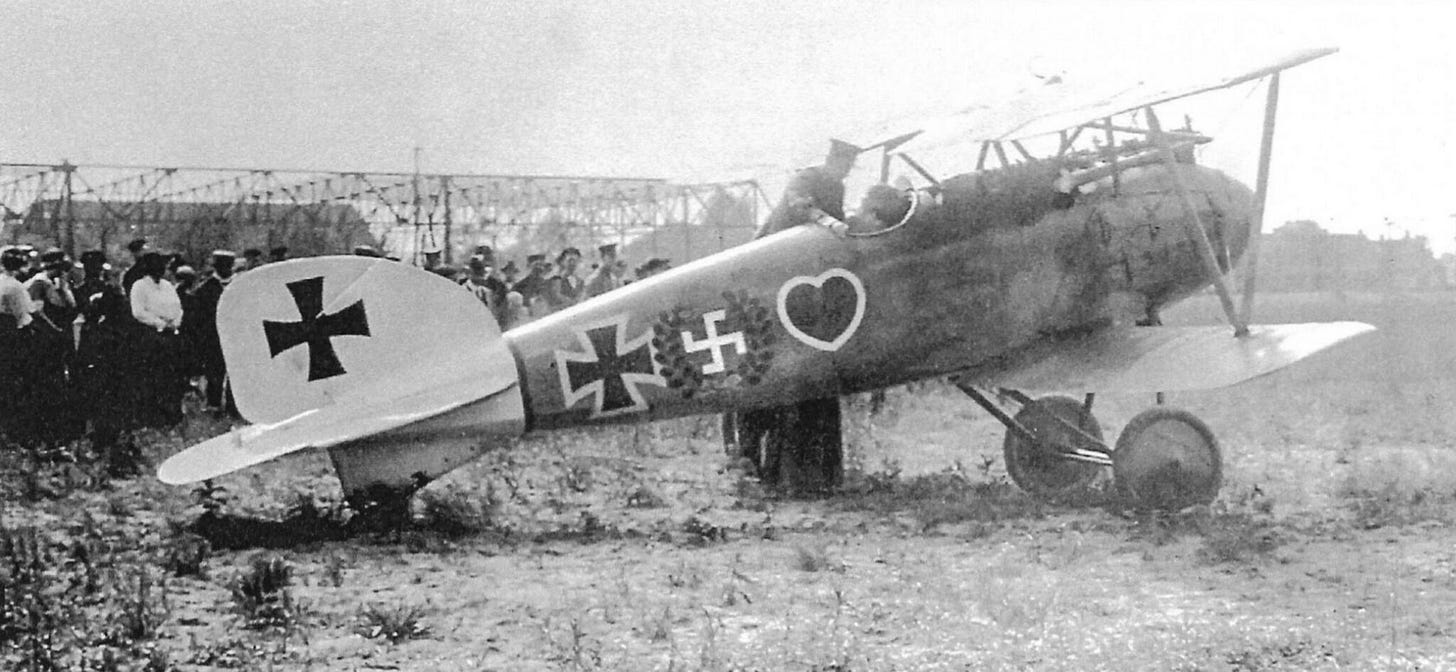

After his 18th victory on January 24, 1917, he made his famed decision to paint his Albatros D.III entirely red..

in part to boost morale, in part as a psychological weapon and open challenge to intimidate his enemies, but in large part because he was a leader who cared deeply about his men—believing that if he were the foremost target, so easily recognizable at a glance, he might use his evasive skills to dodge enemy fire more effectively than many of his men, thereby creating easy targets for his own men to hit as the enemy gave fruitless chase.

Ironically, his men, valuing their leader just as much as he valued them, began to follow suit, with each painting a portion of their own planes red—in large part to take some of this enemy focus off Manfred. This sparked a trend of each ace fighter in Jasta 11 gradually turning their craft into a personalized and distinctive art piece, creating a visually striking unit that became a supremely feared (and easily recognized) force in the skies.

Due to their unprecedented success, April of 1917 became known as ‘Bloody April’, with Jasta 11 claiming an incredible 89 victories during the Battle of Arras, with Manfred himself scoring 21, and his brother Lothar 15. Their fame was beginning to spread well beyond their own national borders.

One can imagine how enemy pilots must’ve felt on seeing this swarm of distinctively painted machines and suddenly realizing the caliber of men they’d become locked into a dance to the death with.. realizing that they may very well not make it home.

In late June or early July of 1917, Jasta 11 joined Jagdgeschwader 1 (JG I), officially forming "Richthofen’s Flying Circus," named both for their brightly colored aircraft and their exceptional use of railway trains for rapid relocation, allowing them to respond rapidly to changing conditions and ensuring these most elite pilots were always where they were most needed and helpful at any given moment... allowing them to strike quickly and unpredictably, significantly enhancing their effectiveness on the Western Front.

The ‘Red Baron’ was now the leader of an entire fighter wing—a collection of many of the greatest or most promising pilots in the nation—and under his expert guiding hand, these units would quickly become the most devastatingly effective air force in the world.

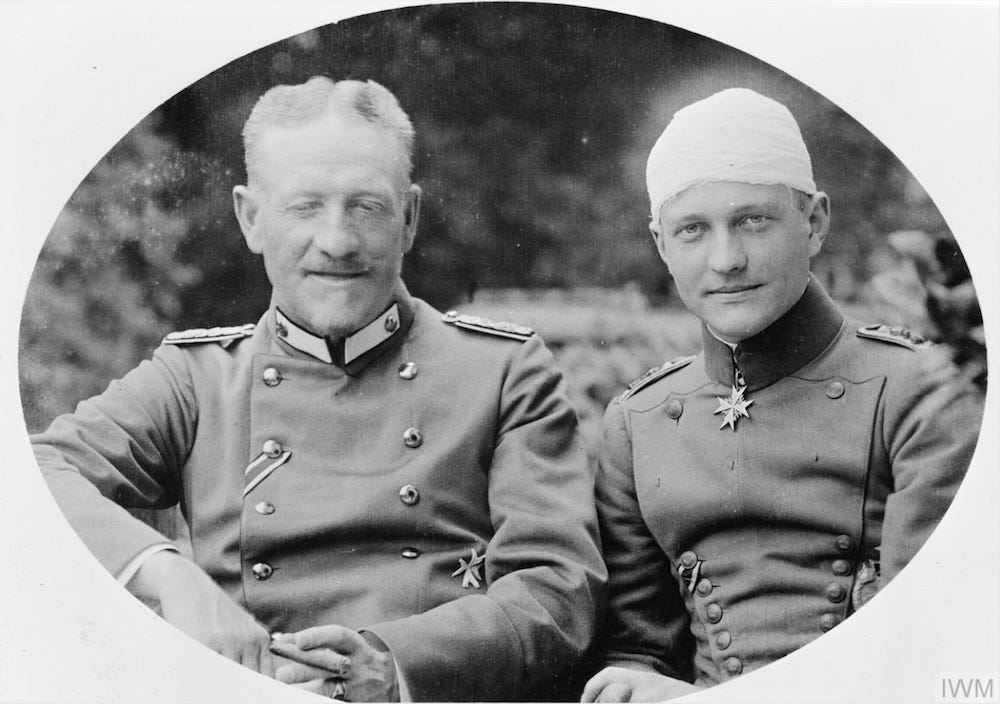

A Bullet to the Head

His tenure as squadron commander nearly ended in its first days, in this July of 1917, as a bullet from an enemy machine gun creased Manfred’s scalp—the smallest fraction away from a kill shot—causing a 4-inch scar that never fully healed. He was able to land his plane safely.. but it’s said that the injury led to a change in his mood and personality, and that as result he’d suffer from frequent headaches and nausea. He was also strongly advised not to fly again by medical professionals,

yet returned to flying almost immediately, demonstrating the type of martial resilience he’d become known for. He’d write about how difficult it became to be grounded, knowing his men were taking immense risks without him.. finding it impossible to endure. Still, the serious injury would quietly plague him, with his most private correspondence confiding that after each combat since the injury, he was in ‘the most wretched spirits’ due to its effects.

Even still, he’d allow nothing to slow his pace—feeling a duty to both his nation and his own pilots, paired with an immense respect and sympathy for the men on the ground in the muddy trenches below.

"But I should despise myself if, now that I am famous and heavily decorated, I consented to live on as a pensioner of my honor, preserving my precious life for the nation while every poor fellow in the trenches—who is doing his duty no less than I am doing mine—has to stick it out."

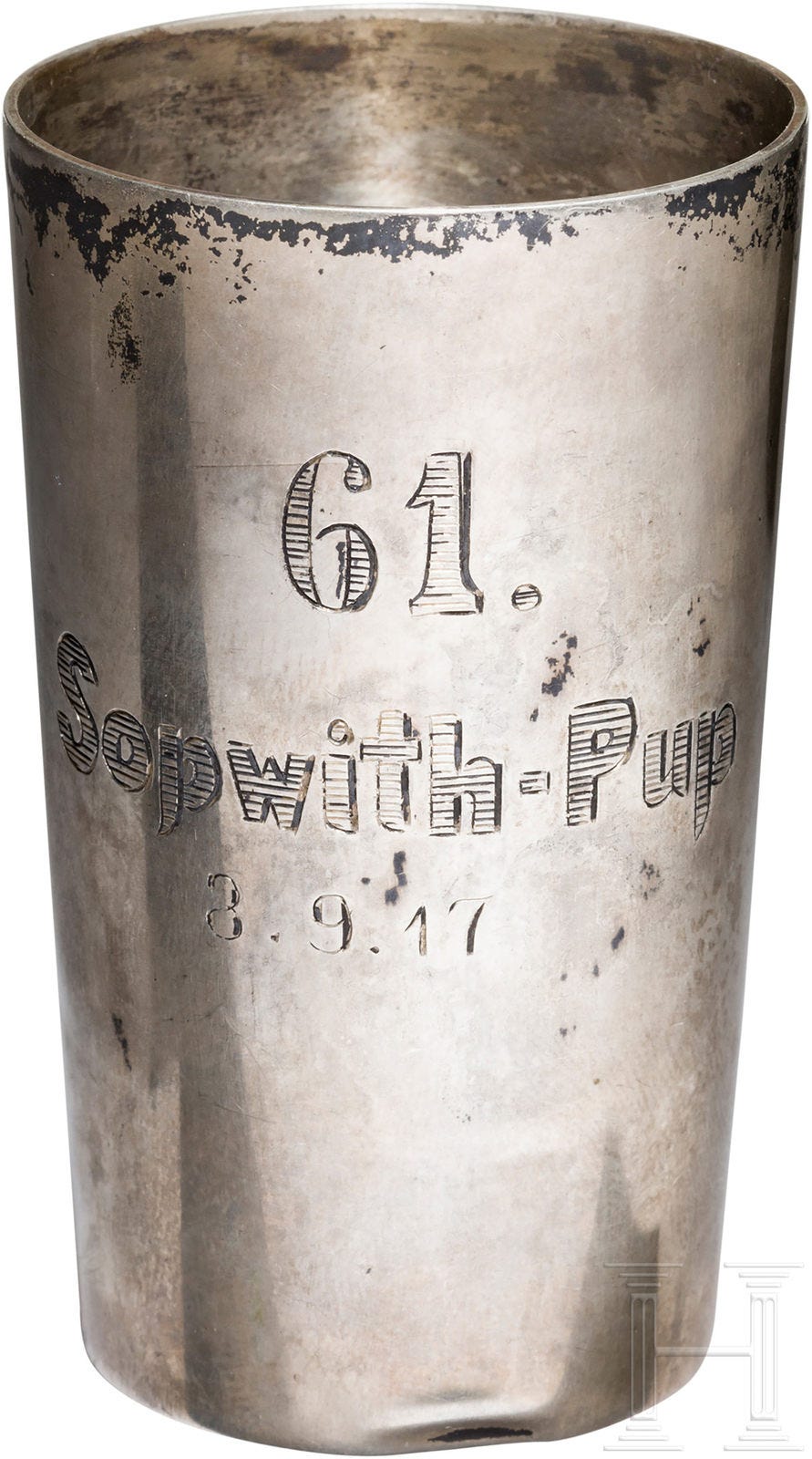

As his kill count climbed ever higher, he’d begin a tradition of collecting trophies to commemorate his scores: a silver cup, for each victory..

until silver supplies became impossibly scarce during the war, at which point he found himself taking small pieces of his opponents’ downed planes instead.

While Richthofen’s ‘Flying Circus’ dominated the skies, another pilot, Werner Voss, was swiftly emerging as both a worthy rival, and valued friend.. a man whose own legend would soon be forged in a truly unforgettable contest..

Werner Voss, and the Greatest Single Air Battle of the War

One of the things that best pushes men to greatness—and then often spurs them ever further—is a friendly and sporting rivalry with respected peers. Manfred was blessed to have this with his great teachers Boelcke and Immelmann, to some degree with his brother Lothar, but most especially with a unique man he considered his greatest ‘threat’ to best him as the highest-scoring ace of the war: the young Hussar from Krefeld, Werner Voss.

Dodging conscription laws from a desire to serve his nation, Voss joined at 17.. proving immediately proficient and being promoted several times at a mere 18, earning the Iron Cross 2nd class. After graduating flight school, he'd be retained to teach it, becoming the youngest flight instructor in the nation.

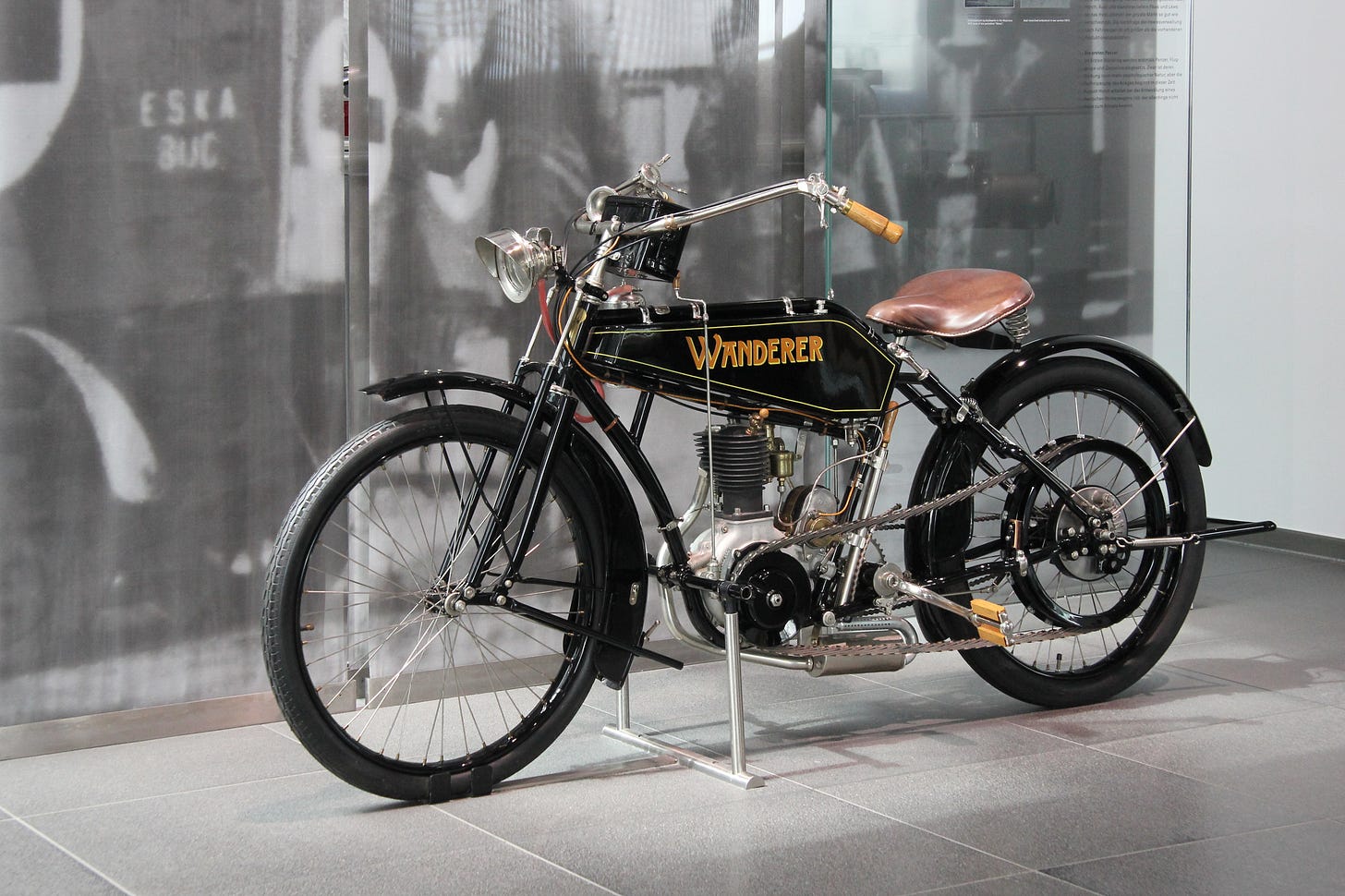

Outside of flying, his other love was motorcycling. Since being gifted this at 17,

he’d develop a resulting fascination with mechanics and engineering.. and even after attaining celebrity ace status, he'd frequently be found contravening uniform regulations in the hangar, working on his flying machine beside the mechanics, dressed in a grubby jacket without insignia.

Richthofen quickly came to so respect Voss’ flying abilities that he’d immediately push (successfully) to get him transferred to JG 1.

They’d been close friends dating back to their service in Jasta 2 in November of 1916... and from the first moment, their relationship had been one of immense mutual respect.

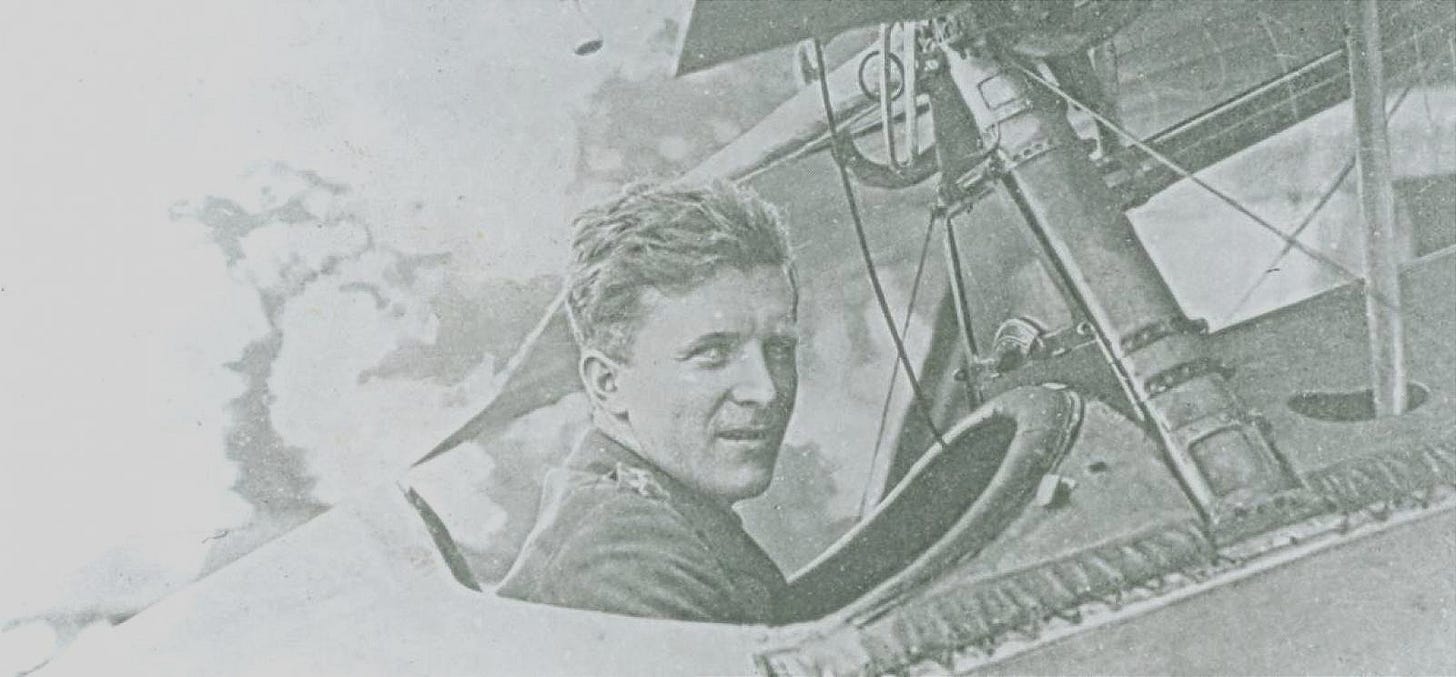

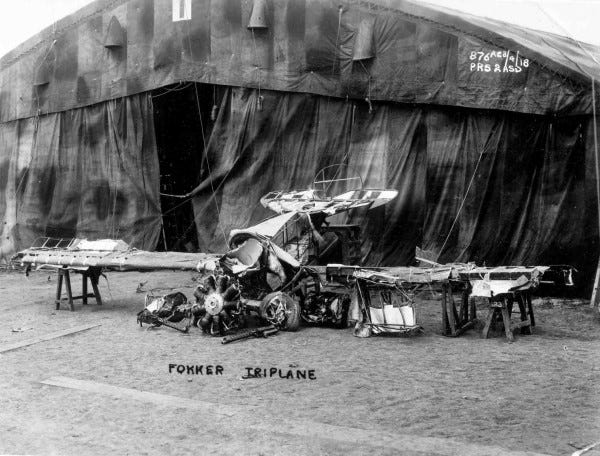

Voss, flying his silver-blue Fokker Dr.I triplane on that now famous date of September 23, 1917, represented the living answer to the question of what happens when you create the most well-engineered machine and place it in the hands of the most comprehensively competent pilot.

Taking to the skies just hours after scoring his 48th victory, he was now just behind Manfred in total kills, and currently scoring at a much faster rate... at this pace, he’d soon be the foremost ace in the world, and all around him couldn’t help but recognize the exceptional talent—Manfred most of all. And perhaps this friendly rivalry was some small part of Voss’ driving force, as he took to the air that fateful day…

With both Germany and the Allies seeking air superiority over the developing Battle of Passchendaele (a three-month battle that would result in over 500,000 casualties), the stakes were high... and Voss, due to his reputation, was now also a hunted man.

After takeoff, Voss’ Fokker triplane—its rotary engine roaring, its increased agility and speed representing a marvel born of German engineering ingenuity—was faster than those of his wingmen, and the distance created between the two was immediately pounced upon by a British patrol, who swooped to engage the slower planes, leaving Voss alone with two enemies just ahead. Hardly a problem for Voss—he used the time to quickly take down the two British planes by himself, with the latter surviving to fly another day only because Voss’ eagle eye had suddenly spotted a new threat, immediately requiring his full attention:

Eight British planes on the horizon, speeding in his direction.

At this moment, it’s possible Voss felt little fear... after all, he may well have been the greatest pilot in the world, and even significantly outnumbered, he never felt significantly outnumbered. Unbeknownst to him, this time was very different—this was a collection of some of the greatest Allied pilots in the world. All eight were aces, their No. 56 Squadron being the highest-scoring British fighter wing.

This would be no standard engagement…

"We were just on the point of engaging six Albatross Scouts away to our right, when we saw ahead of us, just above Poelcapelle, an S.E. half spinning down closely pursued by a silvery blue triplane at very closed range. The S.E. certainly looked very unhappy, so we changed our minds about attacking the six V-strutters, and went to the rescue of the unfortunate S.E."

~ Flight Leader of 56th Squadron, Captain James McCudden

It’s said that he could’ve easily evaded the battle had he so chosen... yet he chose to engage, perhaps believing—not knowing the completely exceptional situation he was facing and the quality of pilots in front of him—that he stood an excellent chance, if he kept his wits about him. Or perhaps, the brave young man simply wanted a genuine challenge, at long last.

And so, what would go down as perhaps the greatest single air engagement of the war began, in earnest... one heroic German against eight highly competent Allied aces—who opened the battle shocked at seeing no attempt whatsoever by their prey to flee, but rather encountering a seemingly fearless man who immediately began targeting all of them.

"By now the German triplane was in the middle of our formation, and its handling was wonderful to behold. The pilot seemed to be firing at all of us simultaneously, and although I got behind him a second time, I could hardly stay there for a second. His movements were so quick and uncertain that none of us could hold him in sight at all for any decisive time ...

I noted the triplane in the apex of a cone of tracer bullets from at least five machines simultaneously, and each machine had two guns."

~ James McCudden

Voss immediately shoots several holes in McCudden’s plane, a Victoria Cross recipient who would go on to earn an incredible 57 kills in the war... and then promptly riddles Lieutenant Verschoyle Phillip Cronyn’s plane so badly that it’s immediately forced out of the fight (and will be later scrapped after he limps back to his airfield, with the man himself suffering a nervous breakdown as a result and being sent home), after he turns into Voss and then throws his plane into a violent spin in a desperate bid to escape more bullets from the German.

For nearly ten full minutes, Voss proceeds to engage in the most skillful dance of attack and evasion, unbelievably putting holes in every single plane on the other side, "never flying in a straight line for more than a second or two, combat so chaotic that every pilot that makes it back to base has a different story to tell in their after-action reports."

Side slips, spins, loops, barrel rolls, zigzagging—Voss seemingly harnesses his every last skill and makes full use of every last trick he might bring to bear, as if possessed, divinely inspired... never holding a straight course for more than seconds, evading British fire and somehow simultaneously spewing bullets at them all individually. He lands a bullet directly into the engine of Keith Muspratt, forcing him out of the engagement... shortly after, Richard Maybery is forced to withdraw as well, with the numerous fresh holes in his own plane making it impossible to fly properly.

During the fray, it’s mentioned that more than once Voss establishes such height and superiority of position that he’d have been free to flee back to German lines... and yet, each time he breaks free, he promptly dives back in.

British ace Geoffrey Hilton Bowman, who’d go on to attain an impressive 32 kills himself, does all in his power to remain in the fight despite Voss’ expert marksmanship and the resulting black smoke pouring out of his SE.5, stating:

"To my amazement he kicked on full rudder, without bank, pulled his nose up slightly, gave me a burst while he was skidding sideways and then kicked on opposite rudder before the results of this amazing stunt appeared to have any effect on the controllability of his machine."

As Voss turns hard to charge directly at McCudden in a head-on machine-gun firing merge by both pilots, Voss’ aircraft was suddenly struck by a starboard broadside burst of machine-gun fire from Hoidge, who was probably unsighted by Voss at that moment… and after this, it was noticed that Voss stopped maneuvering and flew level for the first time in the engagement. Pouncing on this opportunity, British ace Rhys-Davids, who had pulled aside to change an ammunition drum, quickly rejoined the battle with a 150-meter (490-foot) height advantage over Voss’s altitude of 450 meters (1,480 feet) and began a long flat dive onto the tail of Voss’ triplane, which failed to react... almost certainly an indication that Hoidge’s bullet had landed, and Voss was now critically injured.

At point-blank range, he raked Voss’ aircraft with his machine guns before breaking off. A few seconds later, Voss’s aircraft wandered into Rhys-Davids’ line of flight again in a strangely becalmed slow westward glide. Rhys-Davids again fired an extended burst into it, causing its engine to stop, the two aircraft missing a mid-air collision by inches. As the triplane’s glide steepened, Rhys-Davids overran him at about 1000 feet altitude and lost sight of Voss’s aircraft beneath his own.

From above, Bowman saw the Fokker in what could have been a landing glide, right up until it stalled. It then flipped inverted and nose down, dropping directly to earth.. finally smashing into the ground near Plum Farm north of Frezenberg, Belgium, at approximately 18:40 hours.

McCudden, watching from 3,000 feet, recalled:

"I saw him go into a fairly steep dive and so I continued to watch, and then saw the triplane hit the ground and disappear into a thousand fragments, for it seemed to me that it literally went into powder."

There would be debate later whether Voss dropped out of the inverted triplane.

Arthur Rhys-Davids, who’d hit Voss himself twice in the abdomen during the battle, likely just after Hoidge’s shot to his chest, would later express sincere regret at not having somehow brought Voss down alive. Marveling at what they’d experienced on this incredible day, McCudden would famously state,

"As long as I live I shall never forget my admiration for that German pilot, who single-handed fought seven of us for ten minutes and also put some bullets through all of our machines. His flying was wonderful, his courage magnificent, and in my opinion he was the bravest German airman whom it has been my privilege to see fight."

Had he somehow survived this singular engagement, he very well may have flown away the top-scoring ace in the world… and yet, it’d be hard to script a more glorious ending to an ace pilot’s career:

Having—by choice!—fought an entire squadron of the most skilled and experienced British aces for nearly 10 minutes, downing several of them and leaving every last enemy plane with significant damage to show for it, Werner Voss had now justly ascended into legendary status... proving quite possibly the most comprehensively competent pilot of the war—courageous, heroic, and duty-bound to the very end.

Richthofen Ascends to Join Voss

One of the greatest unsung pilots of the age was Manfred’s own brother, Lothar, who’d end up with 40 victories, exactly half the number of confirmed kills of his brother—and who, despite having a much more aggressive and brazen style, would somehow end up surviving the war... and his beloved brother.

Plagued by a head wound much more serious than others knew, having to force himself through the motions out of an unshakeable sense of duty, and sheer love for his nation and his men, some feared Manfred quietly harbored something of a death wish.. or rather, at the very least, had lost that unique instinct that makes men want to so cling to life, and aggressively safeguard it.

A clock was ticking.. and its minutes were numbered.

On April 20, 1918, as Manfred soared the skies of Beaumont-Hamel, France—and as a young Adolf Hitler was perhaps quietly celebrating his birthday while fighting in the trenches below, not terribly far away—Richthofen would score his 79th victory, killing Major Raymond-Barker immediately with a short and masterful burst of fire. His second-to-last kill, on his second-to-last day on earth.

On April 21, 1918, Richthofen led a patrol over the Somme River, chasing a Sopwith Camel piloted by Canadian Wilfrid Reid May. May had just fired on Richthofen’s cousin, Lieutenant Wolfram von Richthofen, prompting the Red Baron to give chase. During the pursuit, he was briefly attacked by another Sopwith Camel piloted by Canadian Captain Arthur "Roy" Brown, also from No. 209 Squadron. Brown dived steeply at high speed to intervene and then had to climb steeply to avoid hitting the ground. Manfred turned to evade Brown’s attack and resumed his pursuit of May, flying at an unusually low altitude, making him vulnerable to ground fire... and at approximately 11:00 AM, Manfred Albrecht Freiherr von Richthofen would be struck by a single .303 bullet that severely damaged his heart and lungs. The exact origin of the fatal shot remains hotly debated, a significant controversy: was it the Canadian pilot Arthur Roy Brown, or was it—as many believed Manfred was far too skilled a pilot to die to aircraft fire unless exceptionally outnumbered—the Australian ground troops, and Sergeant Cedric Popkin of the 24th Machine Gun Company of the First Australian Imperial Force, using a Vickers machine gun?6

Regardless, the damage was done.

Despite being mortally wounded, Richthofen would manage to bring down his Fokker Dr.I in a field near Vaux-sur-Somme, France—however, by the time Australian troops reached him, the most successful and revered pilot of the First World War had slipped his mortal coil.. dutiful to the last.

Arthur Roy Brown reportedly said, "If it had been my dearest friend, I could not have felt greater sorrow," and would rarely speak of the incident afterward.

The next day, April 22, 1918, he was buried with full military honors in Bertangles, near Amiens, France. This included six officers as pallbearers and a salute, including a wreath inscribed "To Our Gallant and Worthy Foe."

The fall of this most accomplished ‘knight of the air’ served to mark the end of an era... and yet, simultaneously the beginning of countless powerful legends that would stoke the fire in the hearts of generations of young men ever since.

Legends never die; heroes live on as ideals of excellence to emulate.. serving a most beautiful and necessary purpose—lifting us upward, pushing us forward..

Immense respect to all of the greats of this prior age:

Well done.. and may you rest in eternal peace.

He and his brother were sons of Prince Friedrich Leopold of Prussia (1865–1931) and Princess Louise Sophie of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Augustenburg (1866–1952), grandsons of Prince Frederick Charles of Prussia.

This medal, presented by Kaiser Wilhelm II, elevated the status of fighter pilots. The award is colloquially known as the "Blue Max," possibly in his honor

A maneuver that allowed pilots to reverse direction quickly during combat, remaining a standard in aviation to this day.

Of course failing to fully take into account varying combat opportunities, difficulty of opponents, or the differences in the quality of planes being flown, or kill verification processes - among other variables

Awarded for his bravery in attacking three German aircraft single-handedly on July 25, 1915

"Trench warfare in World War One was terrible and dire and claimed thousands of lives. Nobody wanted to read or know about that after four years of it. Then along came this dashing pilot of the air and he was a bit of a breath of fresh air, even though he was the enemy.He quickly gained a reputation as being a great pilot and a hero of Germany.

All the Allies tried to get him. At one stage the British formed a squadron to specially to hunt down Richthofen and offered large rewards and an automatic Victoria Cross to any Allied pilot who shot him down.

There has been a lot of controversy as to who did indeed shoot him down and this document is a fairly strong piece of evidence to support the case of Cedric Popkin. But in the scheme of things, does it really matter who shot him down?"

-Tom Lamb

(https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3277958/Mystery-killed-Red-Baron-finally-solved-Final-moments-fearsome-German-flyer-described-time-eye-witness-account-come-light-100-years.html)

This is simply incredible work. You have an exceedingly rare gift for bringing history to life… and what an important gift this is. You honor your creator in using it the way you do.

Heroes!