The Little Known 'New England' of the Black Sea

(and the intriguing connections between Anglo-Saxon nobility and the Goths)

The Gothic people represent perhaps the most compelling and mysterious chapter in history—rising to such immense and wide-ranging power after toppling the Roman Empire, stretching from Spain in the West to their earlier home in the Black Sea region in the East (and very likely much further, if Pinkerton and others are correct about their direct connection to the Scythians)—only to virtually disappear from the historical record around 700 AD, after the combined efforts of their hosted Jewish populations and incoming Muslim invaders upended them.

A great deal of evidence seems to hint that our very conception of 'Royalty' and noble lineage in the Western world largely springs from the great 'Amali' and 'Balthi' (Amalings and Balthings) Gothic ancestral line, and nearly every European nation can point to some strong connection to this sprawling family of peoples—as evidenced in part by incidents like the 'Council of Basel' around 1440 in Switzerland, where representatives from Spain and Sweden famously clashed over which had the stronger claim to ancient Gothic ties.

After the 'Gates of Toledo' were thrown open in 711 AD, and combined Muslim and Jewish encroachment began in earnest, Gothic rulership became displaced, disempowered, and hunted. However, unlike their cousin people the Vandals, who’d held such dominant sway across North Africa and surrounding regions as an aristocratic elite before being practically genocided (according to many scholars) and completely disappeared, the Visigoths, Ostrogoths, and brother peoples were too widespread, and their populations too high, to experience the same total erasure.

And yet, modern scholarship does essentially act as if they did practically evaporate, supposedly leaving little to no traces, anywhere.

But what really happened to the Goths—and what peoples existing on the world stage after their supposed departure shared the strongest genetic or cultural connection to them?

I recently read a work called Conquered: The Last Children of Anglo-Saxon England, by Eleanor Parker, and was surprised to learn something equal parts incredible and unexpected, toward the end of this work. Fleeing from the victorious Normans—who’d allied themselves with Jewish wealth (Jews were absent from Anglo-Saxon England before William the Conqueror brought them in from Normandy and Rouen to fund his war)—the Anglo-Saxon nobles and elites were systematically dispossessed, in such a total and brutally efficient manner that it calls to mind the Goths’ rapid fall from great heights.

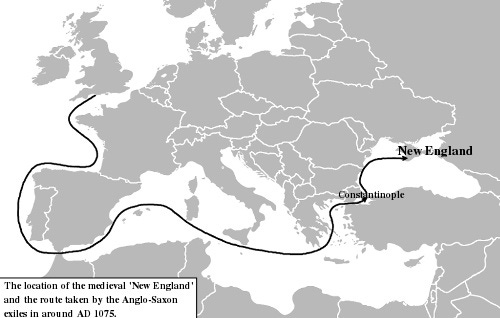

What was so incredible was where these Anglo-Saxon nobles chose to flee to. Many decided to engage in the long Nordic/Germanic mercenary tradition of joining the Varangian Guard, swelling the ranks by several thousand, in hopes of again striking back at their Norman conquerors; but a great many of these nobles remarkably chose to settle on a patch of land with the most ancient connection to both Royal Scythian and Gothic peoples, in the territory north of the Black Sea near Crimea - and even called their new colony 'New England'.

There’s even scholarly debate as to whether these Anglo-Saxon nobles may have mixed with a remnant of Crimean Goths, who were noted to have lived in a small pocket in the region (even continuing to speak in their Gothic tongue, according to the 'Busbecq' account) as late as the 1600s—even the 1800s and beyond, if the account by the Belarusian Bohusz Siestrzencewicz is to be trusted. I might even speculate one step further and claim that perhaps the two groups long knew of each other, and were in contact sufficiently to help cause this area to be their choice of settlement. In Aleksander Vasiliev’s The Goths in Crimea, I noted he speaks of a place called 'Susaco'—which some scholars suggest may be etymologically connected to 'Sussex'.

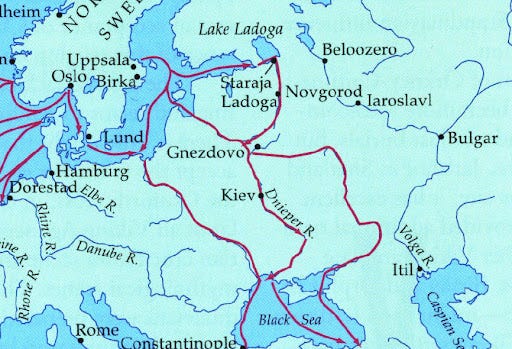

As a descendant of 'Volga Germans' myself, the groups of Germanic peoples that migrated back to this area in the 1800s, I’ve always been struck by the connection of our people with this region—a connection that seems to extend back several thousand years, long before the birth of Christ. Geographically, this makes perfect sense—river systems so cleanly and effectively connect this territory to northern Europe, which seemed to have functioned a bit like a highway system. I’ve long felt that European peoples—extending to the English and their Nordic Viking kin—must have been much more familiar with the Black Sea and surrounding territory than most modern scholars and historians seem to assume.

Though it isn’t simply the Anglo-Saxons’ choice of land that hints at the deepest ties between themselves and the Goths—there’s a great deal more. It’s important to remember the Anglo-Saxons always had a strong conception of Royalty, nobility, and noble lineages—and all of these tended to trace their line back to a 'Woden' (sometimes Odin, Wodan, or other variants, depending on local tradition), a heroic figure said to have led his people into Europe from the east.

They also preserved the 'ric' suffix on so many of their names (Æthelric, Cenric, Wulfric, Sigeric, Eadric), much like the Gothic 'Theodoric the Great', with the 'ric' signifying Kingship and rulership, springing from the Gothic 'reiks', from which 'Rex' is also derived. There’s also a long list of Gothic artifacts that bear striking (and often total) similarities to those found in early Anglo-Saxon Britain—brooches, weapons with specific geometric designs, and the 'great buckle' style found in Gothic graves parallels items found in Anglo-Saxon Kent.

The Old English language of the Anglo-Saxons is perhaps the closest to old Germanic languages of any English language (though it belongs to the Western Germanic branch, whereas Gothic belongs to the Eastern Germanic), and similar terms like 'wer' in Old English for 'man' compared to the Gothic 'wair', or 'fæder' for 'father' relative to the Gothic 'fadar', suggest a deep linguistic kinship predating Anglo-Saxon settlement in Britain. Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People clearly links the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes to northern Germania, and Hengist and Horsa are said to have come from 'German Scythia'. The Anglo-Saxon 'Wuffingas' of East Anglia claimed direct descent from ancient warrior kings whose archetypes resemble Gothic rulers like Ermanric, suggesting shared legends and mythology. Even the Wuffingas’ very name seems to hint at overlap, strikingly similar to common Gothic names like 'Wulfila' or 'Ulfilas'.

Consider this alongside place names like 'Gotham' (Nottinghamshire, England), and that a 'Gotia' once existed in the Crimea right next to a settlement called 'Londina', and the extent of this overlap becomes even more clear.

Genetics also tell the tale: a high incidence of I1 Y-DNA haplogroup heritage existed among both the Anglo-Saxon areas of settlement and those regions most tied to Gothic presence—and I’d suggest R1b-U106 is another tie that binds, genetically. MtDNA too shows evidence of strong connection, with the markers U4 and U5 common to both Gothic and Anglo-Saxon elites, showing powerful maternal-descent connection from the Black Sea into early England.

The exceptional artifacts found in the Sutton Hoo burial (early 7th century, Suffolk), likely tied to the Wuffingas, show weapon- and armor-making techniques strikingly similar to those found in Gothic graves from the 'Chernyakhov culture'—especially the incredible ‘Pietroasele hoard’, dating to the 4th century. The boar motif and dominant warrior ethos are also significant shared features.

In Martin Carver’s Sutton Hoo: Burial Ground of Kings?, it’s noted that such high craftsmanship spread via Germanic elites along migration routes from the Black Sea region to Britain—and I’d suggest this traffic went both ways. The Sutton Hoo burial itself so plainly mirrors Scandinavian and Gothic traditions of boat internment, strongly suggesting greater connection.

The Old English poem Widsith mentions the Goths and their leaders as great heroes of prior ages, and the poem’s inclusion of Ermanric—the 'Gothic Alexander'—seems to indicate these Anglo-Saxon elites saw themselves as part of this same heroic lineage, linking them to their Gothic forebears through shared oral tradition. Beowulf, too, is a deeply intriguing tie that binds, with Gothic-like kings and Hrothgar’s hall echoing steppe traditions, suggesting a cultural inheritance. R. Frank in Beowulf and the Germanic Heroic Tradition speaks of this as further evidence of a 'pan-Germanic elite identity' that stretched across Gothic, Nordic, Anglo-Saxon, and similar peoples. At bare minimum, both Anglo-Saxon and Goth drew from the same genetic pool before portions of them split from one another—but I’d suggest a great deal of this genetic pool also later reunited, post-Gothic collapse, and again became relatively singular.

Finally, I mentioned above how many of the Anglo-Saxons fleeing the Norman incursion chose to join the Varangian Guard—this Varangian Guard is excellent proof of this pan-Germanic shared identity, being composed heavily of Nordic and Gothic warriors initially, until the Goths disappear as a known entity and the Anglo-Saxons make their appearance - at which point this Varangian Guard becomes heavily populated with Anglo-Saxons. Approximately the same people, simply under different names?

And, as I write these words, I also have in front of me a work called The Goths in New England, by George Perkins, who in writing about the early Anglo-Saxon settlers in America flat-out calls them 'Goths', as of his authorship in 1843—without even seeing reason to further explain his word choice.

In short, it’s always felt very strange to me how the Scythians became such a historical black hole, so poorly understood and so frequently dodged and avoided, especially post-WW2. It seemed even more curious how the obvious connections between the Goths and these Scythians were being sidestepped, despite so many historical sources speaking to it. Similarly, it’s long bothered me that the clear connection of the Anglo-Saxons to the Goths seems equally ignored. I’m not sure what we gain from this discontinuity—but it’s obvious how much we stand to lose, and how fractured the historical narrative becomes when we pretend such peoples somehow independently emerged - and then vanished - without deeper ties to progenitor peoples, or descendant peoples.. without being part of a chain of existence.

In coming articles, I hope to speak much further to what I’ve come to see as a cohesive picture - and beautiful storyline - of a single powerful root and it’s many branches.

I hope you’ve found something useful or interesting, here.. and thank you for reading.

What are your thoughts on the onset of the Slavic people? Mainstream historians like to claim that the Slavic people randomly sprang out of nowhere in the 7th century, but this seems just too dismissive. I have always interpreted the Slavic people to be descendents of the Scythians, but especially, the Sarmatian people. This can be evidenced in notable examples such as Sarmatism (Polish noble belief in Sarmatians) or the name Croatia, which I see as derived from Sarmatian (Sarmat~=Carpathian mountains, > Horvat > Hrvatska > Kroatien in German). There is also an Iranic Tablet found in Croatia I believe.

The way I see it, the Slavic migrations of the 7th and 8th centuries were really just a reaction to Asiatic Mongols pushing westward from the East. As for the Germans/Goths (Note Gott-Kings, God kings), I see them as primarily descendents of the Corded-Ware and Bell Beaker cultures, which, although descendents of Steppe-Aryans, their migration happened during the earlier waves like the Yamnaya migrations of 3,000 BCE. Evidence of Germanic peoples already being settled in that region can be seen in Tacitus's work, Germania.

I do think more research has to be done on this topic, especially how the R1a and R1b genetic division along Central Europe came about. Germans have gone quite East as you said with Goths going all the way to Crimea and also the Vikings founding the Kieven-Rus, but I also think Slavic peoples shouldn't be left out of the picture. In many ways, the histories of all Europeans is being purposefully obfuscates, but with Slavs, in addition to these subversive elements trying conceal our history, many Western historians tend to overlook the Slavic people and their stories. I can't entirely blame them as everyone has their biases, but it can sometimes undermine the objectivity of their work. Anyways, I know you are primarily focused on the Germanic peoples and I am amazed at your work, but since you do seem very knowledgeable on the topic, I was hoping you might be useful in helping me find some answers.

Loved this! 🏅Thank you.